|

Sales is everywhere: raising money is sales, hiring is sales, dating is sales, life is sales.

Let me share with you what I have learned about sales that might be helpful to you. I’ll share two main sales principles and a few pro tips. As a friend says "There are no right answers, only pro tips" :-) My Sales Journey I left Kenya in 2015 to go to Silicon Valley to learn sales because I felt my previous businesses would be better off if I knew sales (I’m an engineer). I got an entry-level sales job, which was actually rather hard because everyone I interviewed with said, “you're an entrepreneur. You're going to leave us in a few months. Why would I hire you?” Until a friend hired me for a sales role. Now I'm less bad at a few kinds of sales, specifically cold email outreach to SMEs and proposal driven sales. I don't know much about B2C sales, D2C, complex enterprise sales with many stakeholders, etc. I've raised $10m, sold $200k in business consultancy services, sold $500k of equipment to rural farmers in Kenya, sold $50k of Airbnb rentals and sold about $3m LTV in SaaS so if you've done more than that or in a different industry take everything I say with a grain of salt. Nevertheless, this essay might be valuable to you because I don’t see many people talking about sales honestly. I’ll only share techniques I've used myself. Sales is everywhere: raising money is sales, hiring is sales, dating is sales, life is sales. But weirdly few teach sales. Maybe because we are at the very early stages of understanding human relationships (sales is human relationships). Maybe sales is where astronomy was in the 1500s. We think the earth actually goes around the sun, but we are still hammering out the principles. However, there are some principles of sales which are known. I don't know why they aren't taught in school–seems more useful than trigonometry. Of course, I can’t teach B2B sales in an essay any more than one could teach football or fashion design: which part, which role? It's made up of tons of skills practiced repeatedly. 2 key sales principles 1) Ask Questions is the most important principle I learned in sales. It does three things:

After I discovered the importance of questions in sales for myself I found several sales "gurus" say the same thing: spend 90% of the time asking questions and 10% of the time pitching. 2) Manage my own psychology is the second most important principle. I've had great days where I sell 2 or 3 things and then whole months where I sell nothing. Even more infuriatingly, my effort feels uncorrelated with sales at the micro level. I went a whole year without winning any grants and then won one on a Monday and one on Tuesday. What do you make of that!? Years ago when I started grant writing I went 0-21. Then the 22nd was for $1.2m. So not allowing yourself to sink when you’re low is key. I find 3 workouts a week, occasional breathwork or meditation, parties, latin dance class, entrepreneur mastermind groups and inspirational podcasts like The Game help me manage my psychology. Probably everyone has their own formula for managing their own psychology. Other Sales Principles That Helped Me

After sales, the next step is implementation. A signed contract without implementation isn’t worth the paper it’s printed on. Once the sale is closed the relationship has just begun. But that's a post for another day… sign up for this newsletter at grantco.substack.com to be notified. More sales resources:

2 Comments

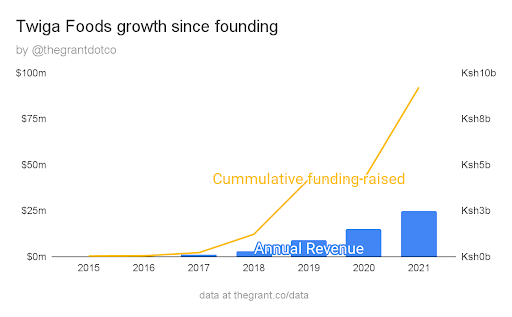

Twiga has raised ~Ksh10b (~$92m) and reached ~Ksh2.7b (~$25m) in annual revenue

But most people don’t know the behind the scenes story. Twiga is a perfect storm: great analysis, great team and great timing. What can we learn from them?

Twiga started with the most difficult suppliers (smallholder farmers) and most difficult buyers (informal markets). Meanwhile, all the other businesses sold to big chain supermarkets like Nakumatt or Tuskies or exported to Europe. So why take the contrarian approach? Kenyan smallholder farmers (<2Ha or <5acres of land) account for 78% (!!) of production in Kenya.

On the buy side, 70% of all produce in Kenya is sold in informal markets.

But no serious company would touch either smallholder farmers or informal markets with a 10 foot pole. Here’s why:

Small holder farmers are hard to buy from: they have small quantities and live down dirt roads, often impassable with big trucks. Imagine actually trying to drive through these “roads”

On my first overnight bus ride in Africa, we stopped at 2am. A truck had overturned and potatoes covered the narrow dirt road. All us men got out of the bus and cleared the potatoes so we could continue the journey. A wonderful story and fond memory—but bad for business.

Informal market buyers have no company registration, no address and can’t be invoiced. You can’t force loyalty or contracts: they buy what they need. If they don’t need bananas today they won’t. And if they can get a better price somewhere else they will. To serve these markets Twiga had to come up with a solution that paid farmers more, sold the product for less and was responsive to market demands such that Twiga would only buy bananas when there was a place to sell them. Oh, and btw, few of these buyers and sellers had bank accounts… Impossible to serve? Twiga had perfect timing. Mpesa mobile money and telecom infrastructure were so ubiquitous that software could finally connect all the pieces together. As they say, software is eating the world… And now we can say “Software is eating bananas”

But it wasn’t all rainbows and unicorns. The initial idea was to export bananas to Dubai. Twiga had an order for 20 containers. But they couldn’t fulfill it bc there were no standards on bananas in Kenya. Farmers didn’t know what they were growing.

Then Twiga brought a truckload of bananas to Nairobi but buyers wanted bananas in bunches, not crates. Buyers would eyeball bananas for size rather than weigh them. Then Twiga had a major insight: Wholesale price was Ksh4 per banana. Marketplace retail was Ksh10. But in housing developments the price was even more. Thus, a huge premium for delivering to the last mile, if delivery could be done efficiently. (For reference, in the US, bananas are ~$0.40/Ksh 45 each.) Little delivery Tuk-tuks enabled Twiga to deliver to micro-vendors that big trucks are uneconomical for.

Fruit vendors no longer woke up at 5am to avoid getting the worst quality produce—Twiga would deliver. Twiga was no longer competing on price, but convenience.

For farmers, Twiga created collection points with transparent pricing on sign-boards. Farmers were paid within 24 hours (!!) by Mpesa

In retrospect, selling to local, informal markets was a boon. By 2020, Tuskies and Nakumatt had fallen into severe arrears with suppliers and closed 92% and 100% (!!) of their stores, respectively. I have friends who delivered $1m (Ksh110m) worth of products to Nakumatt and lost everything.

Lesson: ?antifragility.? With many customers, Twiga was antifragile. If one customer failed to pay, there were more fish in the sea. Meanwhile, suppliers to Nakumatt were lulled into a false sense of security.

Not only did Twiga pursue the most difficult buyers and sellers, but also the most difficult product: Bananas bruise easily and have a short shelf life… why not sell shelf-stable rice?

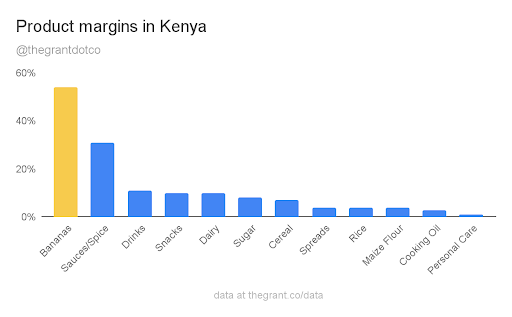

Key lesson for all startups: Bananas have HUGE margins, precisely because they are so difficult. To become a high growth company ?you NEED high margins.? As Amazon CEO, Jeff Bezos, said “your margin is my opportunity”

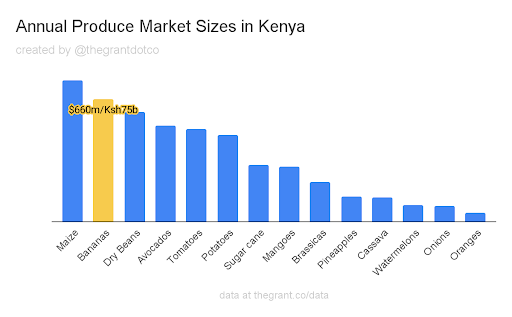

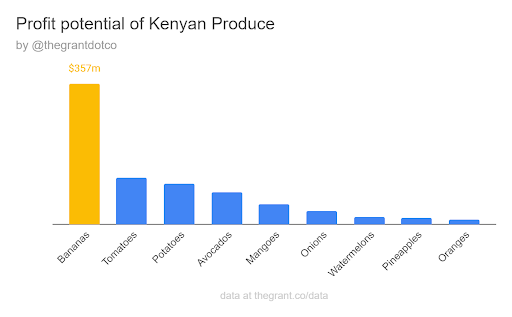

Moreover, bananas have the largest opportunity for distributors as they are one of the largest crops in Kenya

Twiga very intentionally chose bananas. Combining margins and market size, it has the largest opportunity:

?Principle: Anything with high margins is difficult to serve…currently. But if you can serve the market better, maybe if you use some new-fangled technology (hint hint), you can capture those margins for yourself.

That’s exactly what Twiga did. They choose the right time, the right product while leveraging new technology. But they also had the right team: I met former CEO and co-founder, Grant Brooke at a bar on New Years Eve 2014 in Nairobi. For 4 hours he wouldn’t talk about anything but bananas. On Jan 1st. At 2am. That’s focus.

He had plans to become an MP (Member of Parliament). He didn’t do it, ultimately, but it goes to show he was thinking BIG. Outside the box compared to any other expat founder.

Prior to Twiga, Grant had spent years ?researching? informal markets in KE as a Princeton student. ?Lesson in there for would-be entrepreneurs. Before joining Twiga as CTO, @cwanjau was a serial entrepreneur. In 2014, I had hired his company at the time for a project. Particularly notable was his *integrity.* Much respect for him. I’ve never met the other co-founder, Peter Njonjo. With 20 yrs at Coca Cola and becoming President of Coca Cola West Africa, you might think they had it easy. Not so.

Investors in Kenya initially didn’t see the value of Twiga and gave paltry valuations. They only saw Twiga as a banana distributor, not a software company and brand that could rival Coca Cola or Unilever one day.

Peter provided the initial financing with $350k. Then when other investors didn’t materialize he sold his own house to finance Twiga (true story). Fund manager of Lundin (and my former next-door neighbor), Joy Muballe @jmuballe, presented Twiga to Lundin at the seed raise.. But Twiga was rejected by the Investment Committee. So she decided to fund Twiga herself. That decision would return 10x plus for her when she cashed out after 4 years in a secondary funding round. Twiga realized working with smallholder farmers was too costly. They moved to larger farms. But even those couldn’t provide enough supply and now they have started their own farms.

Team, timing, strategy… but there is one more ingredient: Focus.

“We sell bananas. That’s all.” Grant said. Not avocados, or dried bananas or anything else

“Do something specific about something specific. Once you’re successful at that you can do other things.”

Initially Twiga thought “Bananas are tough, everything else will be easier.” But, each produce has its unique challenge: Bananas need to be ripened; Greens need to be refrigerated; Tomatoes are seasonal with market instability, etc. Only now has Twiga expanded to other products like cooking oil and flour.

Only now has Twiga started to expand to tier 2 cities like Kakamega and Kisii and internationally.

Lesson: ?focus? While international aid organizations pressure startups to expand to new countries (don’t get me started!), Twiga at $25m annual revenue, $92m investment and 7 years of experience is still expanding in Kenya.

The timing was ripe: If Twiga hadn’t, someone else would have. Other fruit aggregators are also experiencing massive growth in by adding software @EAFruits ??, @niledotag ??, @khulaecosystem ??, @TaniHubID (Indonesia), @ninjacart (India). Honestly, I’m surprised there aren’t more software-enabled fruit&veg aggregators in Africa. Every country needs one. ?Huge Opportunity.? Parting thought: “Martin Luther King didn’t say “I have a plan” Grant said. “He said ‘I have a dream.’ We had a dream and we hired the people to figure out the plan.” ?Avoid Analysis Paralysis.? If you’re thinking “It’s hard for accomplished people to succeed, why should I even try?” Then please subscribe because the next case study is about an African entrepreneur who had none of these advantages and still succeeded. Stay tuned.

If that was useful to you, consider subscribing to our newsletter for more case studies.

(*Results may vary.)

A Counter-intuitive way to handle due diligence for grants Grantors (and funders in general) want to get ALL of the information about your company before making a decision. While this sounds reasonable in theory, in practice it means due diligence can turn into a fact-finding mission for months and months to the point that the project you planned is no longer relevant. This is horrible for you but also a bad outcome for the funder as they missed out on an opportunity. How to avoid the fact finding mission and get better results. First, let's understand why funders do this even though it leads to bad outcomes for them. Why do they shoot themselves in the foot, so to speak? Human nature. Don’t we all want to have a little more information before we make a decision? We want to look at one more Yelp review, ask one more person’s advice and have the weekend to think over which job offer to take. These are delay tactics because we don’t want to make a decision. It’s not because grantors are bad. They are just human. And humans want to delay. Maybe, just maybe, if they ask for one more document it will make everything clear. It won’t. In fact, the more data they get the more confused they will be. Why did the revenue spike in 2017? You wrote in your 2021 financial model that x would happen but in 2020 it said y. More data never leads to clarity. Data leads to noise. Synthesis leads to clarity. And synthesis is your job, not theirs. Remember the grantor is the customer. Imagine if you went to the pharmacist and they said, well, it sounds like you should take Ibuprofen but here are 2 dozen research papers you can dig through to see for yourself. No. Synthesis is your job, not theirs. Left to its own devices, a few innocent due diligence questions lead to a sprawling fact-finding mission. More and more of your staff get pulled in to answer questions about what happened 3 years ago and distracts them from their real job of building the company. It also uses up the grantor’s time. Your job is to coral this process for the benefit of both your company and the funder. Remember: At the end of the day, the funder needs to make a binary yes/no decision about your organization. If the information doesn’t help them make a yes/no decision it’s extraneous information. Don’t answer questions if it wouldn’t change the funder’s decision. But how to do this in practice? Here’s an idea: At the first meeting, in the nicest way possible, say that you have been in many due diligence processes. You know that sometimes due diligence processes can get out of hand. You want this to be efficient so that you can go back to building and so that you don’t waste the grantor’s time. They have to make a yes/no decision about your organization so let’s focus on questions that would help them make that decision. You might think this sounds rude but it's actually direct. And people respect people who are direct with them. A big complaint of funders is that they can’t trust grantees; grantees are always brown nosing and funders can never tell what grantees are really thinking. Also, people want to work with people they see as peers. Peers don’t grovel in front of each other (seriously, when was the last time a friend of yours groveled in front of you?) Don’t grovel. Which brings me to the next key of due diligence. Meet them in person/video call as soon as you can. If they just send you questions, ask for a meeting to “make sure you understand the context” or you “have some questions you want to clarify and it would be easier in a video call.” People work with people they like and grantors are much more likely to like you if they have seen your face (even on zoom). Meet them before answering questions Even though you originally stated you wanted to keep the due diligence process efficient, grantors, left on their own, will migrate back to their old ways. Don’t let them do it. Push back against excessive questions. If they send you a list of questions that seems excessive you can respond saying any of the following:

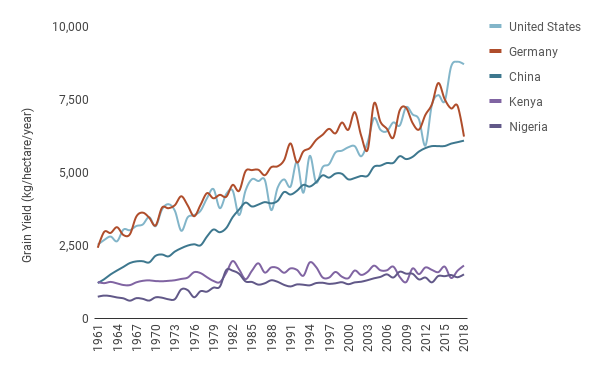

Continue to resist excessive questions. If you can add these guidelines to your due diligence process I expect you’ll increase your win rate while reducing the burden of due diligence and reducing the time it takes to get cash in the bank. More cash. Less effort. What could be better? I just saw the recent Gates Foundation announcement for new grants issued and 2 of 3 are related to training farmers! This is horrible. You might think: How can I be against training Farmers? I am not against the training. I'm against spending the majority of development money on something which actually doesn't deliver value for the farmers. And is actually harmful TO THE FARMERS. Let's dig into these grant awards from the Gates Foundation in detail: the first is a marketplace for goat vets. In theory, this Marketplace will educate Farmers on the different illnesses a goat could have and connect the farmer with a vet who can solve their problem. It's like an Uber or Airbnb for goat vets. But there's two big problems here. One, Uber for goat vets is never going to work as a sustainable business. Why? The GoatVets platform will be disintermediated. Marketplaces only work when you have to interact with a different seller each time. Every Uber I get is a different driver. Every Airbnb I visit has a different host. Every product I buy on eBay is from a different seller. GoatVet will be disintermediated because once Farmers get matched with a vet once they won't go through the platform anymore. Why would they pay marketplace fees when they already know the vet? This goat platform won't make any money and it won't be sustainable. And if it’s not going to be sustainable, why fund it? It’s going to be a money pit if donors do try to prop it up. Mark my words. Okay fine, GoatVet is unlikely to work but that’s how innovation is, right? That brings us to the second point. GoatVet is specifically looking at training Farmers instead of helping Farmers increase their income. This is the problem with all farmer training and why I am so against this. The problem is not that farmers don't know; it’s that they've no place to sell their goods for a fair price. Shouldn’t this be obvious to grantors? Farmers can’t make more money if they can’t sell more products for a better price. This is basic mathematics: Revenue = #products_sold x $price_per_product (Note that this equation is number of products SOLD, not number of products PRODUCED. Farmer training, in theory, increases number of products produced. What we need to do is help farmers sell MORE products and/or for a HIGHER price.) Let’s step back for a second and give some context for what happens on a farm. Farmers all harvest/slaughter their goats at the same time because they plan according to the seasons. This means there's a glut in the Market at one time. The poorest farmers sell when the prices are low. They have no way to preserve their food. The goat meat (or tomatoes or whatever) is going to rot if they don't sell them right away. Then because of poor market linkages there's many middlemen before it actually gets to an end consumer. And because of poor government policy and onerous laws that should be repealed, it's virtually impossible for a smallholder farmer to sell their own produce at scale or export it. There is no way for a small scale farmer to deal with the bureaucracy of aggregation and export. And THAT is what grantors should be solving. Let's go back to the goat farmers. If they have good meat what refrigerator exactly or freezer will they put their goat meat into? What about their goat milk? There's all kinds of government regulations which prevent Farmers from aggregating their milk and selling in supermarkets where they could actually make money. All the money that is spent on Farmer training should be spent on helping Farmers sell their product. If this grant was for something that helps Farmers get their product to customers then we might have something. At first Farmers could sell on the local market. Then once they become competitive they might even be able to export at a premium price. But that's not what this grant is for. But it gets worse. If you train Farmers to produce better products then they will hopefully produce more of it. Yay. But now what? Now all of their neighbors are producing more of that product. Now they have more competition. Supply and demand. This is basic economics. If people produce more goat meat and there's no way to transport to market then the price of goat meat will go down. Farmers might even make a loss. Let's look at another Grant funded by the Gates Foundation. This one for Equity Bank where they're creating an integrated digital platform, EquiFarm. It sounds a whole lot like Safaricom’s collapsing DigiFarm platform. And countless other farm apps in the graveyard like m-farm. The idea is that Farmers will get tips on farming and buy insurance products. Why is a bank teaching Farmers how to farm? Why would Equity Bank, in a centralized way, understand what Farmers need in very different parts of the country with very different growing conditions? Why are we insuring Farmers instead of increasing their income? So why do grantors do this? Well if you look at the data you see that in developing countries Farmers are far less productive than developed countries. Like 5x less. Source: World Bank

And this is even though developing countries near the equator get about twice as much Sunshine as farms in North America or Europe. So the grantors say “if only we could increase yield then all farmers in Africa will be rich!” If only it were so easy! You can't just plug numbers into Excel and magically increase farmer income. If you don't improve the supply chain to market you don't increase sales and you're doing nothing. And possibly making it worse. All the time Farmers spend in training learning "Innovative Smart Systems" (lol) is time wasted they could be farming. Or watching TV. Or drinking a beer which frankly would be a better use of their time. At least if they drink a beer at the bar they might meet someone who can buy their crops. So why do Grantors keep doing this? The reason is that they're afraid to fund Capital Expenditures like processing equipment that can make farm products shelf-stable. To increase sales for farmers you need to somehow preserve their products such that when they pick their tomatoes they don't all rot at the same time. You need to make tomato sauce. With your mangoes make dried mangoes. With your goat you need to make goat sausage. With your french beans refrigerate them. But here's the thing. In order to do that, in order to have any storable, value-added products, you need to have factories. And factories need CapEx. And granters are allergic to CapEx. (I should pause for a moment and say that not ALL grantors are against CapEx. I have worked with some very fine grantors who bravely went to their board to advocate for companies I work with to spend on CapEx. And they were successful. So I know there is hope for grantors to change and make better funding decisions.) Why are grantors generally allergic to CapEx? Because at the end of the grant program some poor entrepreneur could decide to sell the equipment and actually make money. Get a backbone! If you want to solve The World's problems is not going to be easy. You're going to have to go to your board and tell them that CapEx needs to be funded in order to create value-added products in order to increase income for farmers. Otherwise, it's a waste of time and a waste of breath. And it's a waste of grant money so grantors should care as well. Is farmer training EVER useful? Sure, but that's when (and only when) the market is buying so much produce that farmers can't keep up. And even then a little training goes a long way. We don’t need broad-based training for everything. For any given crop under specific conditions of a Farm there are one or two bottlenecks that need to be addressed; the training needs to be extremely targeted. Further, there are far more cost effective ways to train farmers. Look at the Ugandan YouTube channel Farm Up where one guy posts videos getting close to 0.5m views each. Surely this wouldn’t cost more than $100,000. Or Shamba Shape Up TV show where you can reach 9m farmers per week for around $10,000. Meanwhile, EquiFarm training app will only reach 200,000 farmers initially. They claim they will reach 2m at scale (which I’m skeptical of) and will cost Gates Foundation around ~$1.5m. Really? C’mon people. What happened to being data-driven? What makes this even sadder is that Gates Foundation is usually considered one of the “smart money” grantors. So let's stop this Insanity. Stop training farmers. Instead, help farmers increase their income. Finance the creation of value-added products. Pay for the CapEx needed to get these projects off the ground. Stop training farmers. Please. 0th Law: Tell a story. There are human beings reading your grant. Intrigue them, teach them something new, make them laugh at least once. Don't bore them.

————————————————————————————————————- 1st Law: Follow the rubric. Title your sections according to the point that they want covered. 2nd Law: You never get a second chance to make a first impression. Make sure the design is good. If Steve jobs were to design your proposal how would it look? 3rd Law: Under promise, over deliver. Better to project 10% increase in income and achieve 12% than the other way ‘round. 4th Law: Make good use of your time. A $1m grant doesn't take 1000x longer than a $1,000 grant. Don't bother. Exception to the 4th Law: the $1000 is the price of admission to a $1m grant down the road. 5th Law: Grants take 2x as long to get as you'd think to write, go through due diligence, etc. It took up to 18 months for me to receive the money from a grant we won once. By then the grant was hardly even relevant to what we were doing. 6th Law: Grants don't plug cash flow issues. They make them worse. Most grants won’t pay you until after you spend the money or at best they will send you money upfront, but you never know when you’re going to get the money so you can’t depend on it. 7th Law: The more you get, the more you get. At first you won’t get anything. Once you start winning grants it’s like you’ll need an umbrella just to protect yourself from the rainstorm of grants you’ll get. Like the Nobel prize, throwing a life preserver to people who have already made it to shore. 8th Law: Get women and people of color on your board of advisers. All male, older, white board has bad optics. If you are serving women in Ghana, then, for God’s sake, have at least one Ghanaian woman on your board. 9th Law: Human brains work by analogy. Throwing 12% more facts at people, overworked by an average marginal Work Index of 6.1 won’t help you win grants. Write a case study of someone who was successful who did something similar. Example analogy: We are Toms Shoes for Soccer balls. Easy to understand that the impact will be huge. 10th Law: Repeat the same numbers over and over. Not new numbers. There is a temptation to say 31% of children are malnourished, 16% are stunted and 5% are emaciated. Just one number. We get the point. Children are in trouble. 31% are malnourished, 31%, 31%. 11th Law: Humans can remember 3 things. What 3 things do you want them to remember? Usually, I want them to remember 1.) my organization’s name, 2.) their money will make a big difference for us, and 3.) we have an innovative solution. That’s it. If they remember those three things the day after they read my application, I win. To get someone to remember your name don’t just say your name over and over. Tell a story. “The story few people know about how we started [insider gossip heightens the interest in the reader] is that I was sitting on the side of a brook and, suddenly, I had the idea! I was so excited I fell into the brook. That’s why we are called Brookside Dairy.” Now the reader will never forget your name. 12th Law: Have your Docs in a row. Get it? Docs? Ducks? Yeah, have everything lined up. Here’s the Grant Document Checklist I send to my clients. 13th Law: You need 2-4 hours of uninterrupted time to do grant writing. I often do it at night when my employees are gone. 14th Law: No acronyms, no 50 cent words, no jargon. Exception: well-known acronyms like USAID, HIV. 15th Law: Be poetic. 16th Law: Grant management is even harder than grant writing. 17th Law: Outsource and delegate. 18th Law: Look for global maxima. Is this the best grant you can apply for? Or is there one that is a better fit? Scan the list of all possible grants that I share with my clients. 19th Law: Invent/reclaim a new word. Easy to be the best at a new term you coined. I guarantee you I have the best 20 Laws of Grants in the world because no one else has done it. 20th Law: WIIFM. What’s in it for me. That’s all every human being wants to know. What are you giving the grantor that is worth $50k or $5m? How will you make them look good? Bonus Law: Thank people when they help you and they are likely to help you again. If this answer helped you, give some thanks by sharing with someone who you think will also benefit from it. Pay it forward. TLDR there is a method to the madness! Choosing a career is one of the most maddening, stressful activities we must engage in as young people. How do we balance the need of money and desire of fulfillment? How do we plan for a future that might be totally different in 10 years? I know the challenge too well. When I left a tech startup in 2017, the world told me I should be in management consulting, but it didn’t feel right to me. I left Silicon Valley and drove south on my motorcycle. Where to? I was going to drive south until I figured out what I wanted to do with my life. I made it all the way to Peru. All the while I asked: What am I supposed to be? There were no easy answers but after months of motorcycle riding, I discovered there were a few guideposts to help me find a career (some guideposts more hidden than others). Did it work? Yes, this story does have a happy ending. I found the career I wanted (and the partner of my dreams, too). I’m making more money than ever before while loving my job. The sun broke through the clouds. Here are the guideposts that worked for me. I hope they help you too. At the end, there’s a tool to help you brainstorm career ideas keeping these guidelines in mind. Let’s begin. Is it interesting for 5 to 10 years? To do anything important, you have to be patient. This is a result of compounding. You’re probably familiar with compound interest at the bank. The power of compounding happens in a career as well. If you’re not in the career for at least 5-10 years you can’t expect to get compound interest. Compound interest happens when someone you meet in the first year of your career pops up again nine years later with a big job for you. If you didn’t stick around for those nine years, you would miss out. This isn’t about being passionate about a cause. It’s not about the money I can make this year. Rather, can I be interested in this kind of work for years on end? Which leads to the next guidepost... Do you enjoy the day-to-day? Lots of jobs seem sexy and fun. But would you like them? Travel blogging looks so romantic. But it’s super competitive, low pay, and draining as you have to keep moving from country to country to get more content. The more successful you are, the faster you have to go to keep up. When I was in college, I liked the idea of being a scientist. I liked the idea of chasing the truth and sparring with collaborators in a university. But I hated the day-to-day. As a research student, it’s a lot of measuring exact quantities, following precise protocols, and waiting around. I didn’t get excited. I didn’t meet a lot of different kinds of people. So what do you love on a day-to-day basis? Here’s what worked for me: before working in Silicon Valley I ran a Biogas company in Kenya for 5 years. My day-to-day was riding my motorcycle on dirt roads visiting fairly poor farmers, and hearing about their life stories over more cups of chai tea than I can count. Basically, I got to do endurance motorcycle riding while visiting people very different from me, who completely blew my mind. Find a job where you enjoy the day-to-day, not just the idea of it. Have a life you look back on with pride Imagine yourself on your deathbed. Will you say, “I’m proud of the life I lived” or not? The dollars in your bank account that you can’t take to the next world won’t be on your mind. You will remember the relationships you had, the difference you made for other people, the impact your life had on others. The times you laughed, the times you cried. Many prestigious jobs are never-ending loops: you work hard, get a promotion, get more pay, work harder, etc. But what was the end goal? Work hard so you can work harder in the future? It’s like a pie-eating contest where the prize for winning is more pie. Enough of that madness! Exit the loop. Do what matters (to you). Maximize Learning Learning makes the present interesting and makes you prepared for a great future. You’ll be happy today while building skills that give you optionality tomorrow. They say that the trade-off between working at a big company vs. a startup is that they pay you more at a big company, but the learning is slower. At a (small) startup, you learn on the fly about a range of things. With the effects of compounding, having a slower learning rate can mean that some people get left behind at the age of 55, unhirable, untrainable, a career killed one “safe” decision at a time. Find your tribe There are some people that you think you want to be around, they are popular or attractive or rich or seem to have exciting stories, but once you’re around them, you’re bored, you're embarrassed for them, or they just don’t have the same values. Find a career surrounded by people in your tribe. You only have one life, and a large part of your adult waking life is with your colleagues. I choose to start fundraising for entrepreneurs in developing countries. Not non-profits in the US, but for-profit organizations mostly in agriculture, energy and tech in Africa. Entrepreneurs have so much energy, optimism, and courage that makes me excited as well. And working in a developing country heightens that experience.

Those are my people. Who are yours? Make enough money that money is not a constraint Money’s just a tool. But life without specific tools would be...hell. Hammering a nail with your fist is painful, bloody, and dispiriting. Think of money the same way. Some industries just don’t pay well. It’s not a matter of intelligence; it’s just the nature of the industry. If Bill Gates had decided to become a high school teacher, he probably would’ve been a good teacher, but there’s no way he would make the same money. As I was applying for college, I remember telling my (poor) uncle that I was considering either philosophy or engineering major. He, a professor of philosophy, said: “It’s all well and good to follow your passion. But in my experience, as a grad student with nothing in his pocket, only able to afford discounted wine and the cheapest sandwich shops, and years paying off grad school loans on a professor’s salary, I wouldn’t recommend that path.” Always the eloquent speaker. You don’t need to be a billionaire to be financially free. But a good way to have a healthy wealth (not necessarily high income) is to choose a path with minimal downside and great upside when things go well. If you are patient for 10 years (see the first guidepost) eventually things will go really well. That’s why I like grant writing. When we help an entrepreneur raise capital we win big. This aligns our interests with theirs. Working for a tech startup and getting equity is another way to have a big potential upside. The challenge is that all your eggs are in one basket, therefore... Diversify your income (Become Antifragile) Let’s compare an employed banker to the Uber driver who drives the banker to work. Which one is better off? The banker makes more every month, and her salary is consistent. Meanwhile, the Uber driver’s income varies from month to month. But consider the freedom the Uber driver has. He only works when he wants to. If he wants to take off work for his son’s football game--no problem. Meanwhile, the banker has missed every single one of her daughter’s cross country races. Then, suddenly, the economy crashes and the banker is laid off, and she can’t get a new job. The banker was lulled into a false sense of security. The steady paycheck was not a sign of stability. It was a sign of fragility. The banker only had one revenue stream, and when she lost it, she lost all of her revenue. Meanwhile, the Uber driver only lost one customer. The banker now can’t afford her mortgage. The Uber driver, knowing that he could never count on any given month, never lived beyond his means and knows he will never lose his cozy house. Diversify your revenue to become Antifragile. If you are employed, you have one client; if you're a consultant, you have many. (Antifragile is a book I can highly recommend.) Choose a rising tide “A rising tide floats all boats.” The first investor in my biogas business worked on Wall Street in the 1990s and early 2000s. He said it was like shooting fish in a barrel. It was so easy to make your quota and get a bonus. The phones were ringing off the hook. Then in 2006, he retired early. Just in time, too! One year before the market crashed. My investor experienced a rising tide. Choose a career in a market that has a rising tide. Struggling against the current is wasted effort. Better to be thoughtful, take your time to choose the right market. “Work smarter; not harder,” my (rich) uncle once advised me. This is not something you can do overnight. Talk to a lot of people and do a lot of reading. Think 10 to 20 years into the future. Let’s take an example. Is it a good idea to become a professor now? I’d say no. Many universities will go bankrupt, which means a lot more supply than demand for professor jobs. What will be rising tides in the future? I think developing countries will be one rising tide. Now that countries in Africa are mostly politically stable and growing rapidly, the amount of capital flowing to these parts of the world will be massive. Africa is like China was 30 years ago, but without the language barrier. Here’s another way to look at it: Agricultural productivity in the UK, a country blanketed in snow much of the year, is 5x greater than Africa, a continent with two growing seasons. This is a consequence of underinvestment, not the fundamental nature of the land. That’s why I’m bullish on capital raising for companies in developing countries. We will be well-positioned to help money in developed markets go to developing markets. Conclusion During my motorcycle trip, I ranked my career ideas against the guideposts listed above. That’s why I started a Grant Writing business. If you made it this far, maybe you're the kind of person who would also enjoy making such a spreadsheet to assess your career options. So I made something specifically for you. Yes, you, the one with two thumbs reading this right now. Here is a spreadsheet you can fill out for yourself. And if you’ve decided you also want to be a grant writer, consider applying to work with us at thegrant.co/careers If Bitcoin reaches a price of $100,000 to $200,000, there will be more crypto-billionaires than *all* other kinds of billionaires...Combined. BTC reached nearly $65,000 this year, so Bitcoin at $100,000 is not that far off. Cryptocurrency will change the world in many ways but there’s one question no one seems to be asking: How will cryptocurrency wealth change philanthropy? And of particular interest to organizations looking to raise capital, what will crypto-philanthropists donate to? Let’s start with an example Crypto-Philanthropist Vitalik Buterin, creator of the second most valuable cryptocurrency, Ethereum, and worth an estimated $21B, recently made his first high profile donations totaling over $1B. His gifts included:

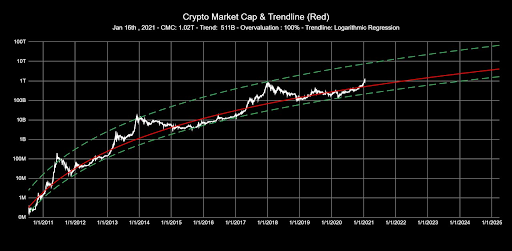

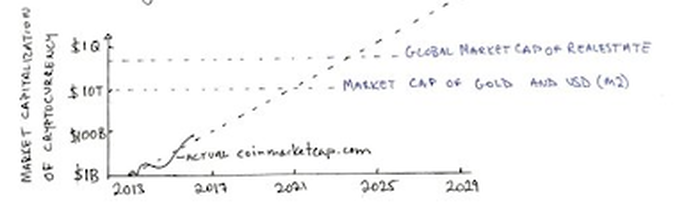

Life extension, artificial intelligence and autonomous city-states. These donations are...unusual. Let’s talk about some areas that crypto-philanthropists might focus on. Aligned Causes “Most of the people who bought crypto early on — they’re believers in the power of technology to change the world. They’re interested in the ethos of crypto in many cases, and I suspect that they would allocate their capital towards more things in that vein.” -Brian Armstrong, CEO of Coinbase, Interview with Tyler Cowan Crypto’s “ethos” has traditionally been libertarian: skepticism of fiat money and financial systems, a belief in privacy and anonymity as enabled by cryptography, in favor of minimal government regulation and taxation. Most the largest number of grants in the crypto currency space seem to be for other currencies and protocols like grants from Solana, Human Rights Watch and Kraken cryptocurrency exchange. While not everyone in the crypto-community today holds these views, remember that those who were able to accumulate the most crypto wealth necessarily got started right in the beginning. And to start in the beginning when Bitcoin was a risky bet they had strong philosophical motives. Risky Bets Crypto-Billionaires made their money by taking a risky bet. Their philanthropy might be characterized by similar levels of risk tolerance. Buterin’s donations (life extension, general AI, charter cities) suggest the same attitude is being applied to their donations. Risky bets in grant making couldn’t come at a better time. Traditional grant makers are criticized for being too adverse to moonshot proposals, funding incremental, low risk projects for older and older researchers. At the NIH, for example, the average age researchers obtain their first Research Project Grant was 35 in 1980; in 2016 it was 43. The crypto-community is younger. Nearly half of millennial millionaires have at least 25% of their wealth in cryptocurrencies. Cryptocurrency investing drops off for those 45 and up. It’s likely that early crypto-investors were young. A number of teenage crypto-millionaires have identified themselves. Fast decision making Money will also move faster. Institutional grantors take months to decide (6 to 18 months in our experience). Bitcoin has often risen or fallen 10x over the length of typical grant cycles. Those timelines won’t be acceptable for crypto-billionaires obsessed with the speed of transactions. But is fast grant making even possible? A number of tech leaders just experimented with grant speed in a Covid philanthropy project, FastGrants. As they describe it: The original vision was simple: an application form that would take scientists less than 30 minutes to complete and that would deliver funding decisions within 48 hours, with money following a few days later. This timeline would be radical to legacy grantors, but it’s natural in crypto. Prizes rather than grants With a grant, money is given to undertake a project. With a prize, money is awarded upon a project’s completion. Prizes have the virtue of always being tied to results. This has its parallels in the workings of cryptocurrencies themselves, where in currency is awarded to miners as a block reward for securing transactions. Prizes are already being seen in one of Balaji Srinivasan’s projects, 1729, where cryptocurrency is given to the winner of a prototyping challenge. For example $100k was granted to a decentralized inflation calculator. Again, a rather unusual grant topic. We would never see USAID or the Gates Foundation fund. And yet inflation is one of the biggest problems in the world, a regressive tax that poor from being able to rise up. Increased Pseudonymous granting Bitcoin was born out of the cypherpunk community of the 1990s. “Privacy is necessary for an open society in the electronic age” their manifesto reads. Most crypto-traders are pseudonymous. We do not know the person associated with almost any wallet. Crypto-billionaires may value their anonymity, both for legal and personal reasons. So they aren’t expecting their names on buildings, nor are they claiming charitable deductions. For example, the Pineapple Fund has donated $86m in bitcoin. We know exactly how much money they have donated, when they have donated, and to whom they have donated at this address on the Bitcoin blockchain: 3P3QsMVK89JBNqZQv5zMAKG8FK3kJM4rjt. But we don’t know the Fund’s benefactor. The next John D. Rockerfeller might be a string of numbers and letters. International Giving Only a small portion of US giving goes to international organizations, 6% according to Charity Navigator. But cryptocurrency is international. The community believes in the egalitarianism that emerges from cryptocurrency’s location independence: It doesn’t matter who you are or where you are; you can still buy cryptocurrency. Whereas grantor like USAID or Gates Foundation often specify which country someone must be registered in to receive grants, crypto grants often don’t care at all which country someone is based in. Effective Altruism Effective Altruism (EA), which encourages people to maximize the amount of good they do in their lives, is also rising in popularity in the crypto-community. A number of Buterin’s investments were connected to EA: MIRI is a favorite charity of EA, and he also made a donation to GiveWell, EA’s default charity evaluator. Another high profile crypto-billionaire, Sam Bankman-Fried, publicly identifies as an EA. He plans to give the vast majority of his wealth (now over $10B) to effective causes. Solving philanthropy’s Impact Crisis Right now, there is a quiet crisis in measuring impact in development projects. Here’s the problem: Let’s imagine that I receive two grants to plant trees. At the end of the year I report back to both them that we planted 100 trees. Each of those grantors now reports on their website: we funded the planting of 100 trees! But if you add up the claims on their websites that comes to 200 trees. Where did those extra trees come from? Obviously grantors try to prevent this sort of thing from happening, but it’s often difficult, especially as results get tangled up together (one pays for the labor and the other pays for the seedlings, for example). There’s also the additional problem of time scale: if 50 of the trees die the next year, neither grantor may ever know. Do they ever revise their websites? Unlikely. Crypto grantors would never stand for this. The point of the blockchain is you know for sure how much money is in each address. Could there be a Blockchain-ish way to enable grantees to certify the impact for a project? There might just be! NFTs are a smart contract on a blockchain to certify digital art or collectibles. This could be the same for impact. All impact these days is presented in a digital format (PDFs, Spreadsheets, dashboards, etc)--why not put it on a blockchain, just like jpeg NFT art? Some NFT art is just so satisfying, right? With an NFT, the seller, who gets paid in cryptocurrency, can then pay their subcontractors in cryptocurrency. If we apply this to philanthropy, this could solve a lot of reporting and transparency issues. If grantees use crypto currency to pay their subcontractors, the whole process of grant reporting would be as easy as pulling data from the blockchain. So when is all this going to happen? If anything holds true in the new world of cryptocurrency wealth, it may be the tendency of billionaires to hold out until most of their growth potential has past. Tech billionaires typically do most of their giving after they leave the company they’ve created and begin to liquidate their stock. Cryptocurrency investors still see an enormous amount of growth potential, so have little interest in cashing out now. But cryptocurrencies can’t grow forever. In fact, if we project the growth curve forward it looks like the growth is slowing down and by 2025 or 2030 most explosive growth might be over: In 2017 I predicted that cryptocurrency would reach a market capitalization of $10T. It has reached nearly $4T already this year (up from $100B when I made the prediction) so my prediction wasn’t that far off. When will crypto-billionaires really start donating? Let’s put some rough numbers to it: People who will become billionaires in cryptocurrency were probably between 20 and 30 when they invested around 2010. Now they are 30 to 40. Philanthropic endeavors tend to take off between 40 and 50. Finally, cryptocurrency will be a mature asset class (not growing in value as fast) in 5-10 years as well, which encourages people to spend rather than hold. So 2025 to 2030 is when we might expect philanthropy to start seeing the full influence of crypto-wealth.

What should I do to prepare? Here's a starting point:

Examples of Crypto-Grants My experience as a grant reviewer. How many times have you wondered “What does this grantor want? How do they decide?” I know, I’ve been there. I’m a professional grant writer. Recently, I had an opportunity to sit on the other side of the table and serve as a grant reviewer. We had to do a sub grant of roughly a million dollars. We accepted proposals, evaluated them, had video interviews with the finalists, selected one winner and, unfortunately, let the rest know they lost. What an experience! I have new sympathy for the challenges grantors go through. Walking a mile in their shoes showed me some of the mistakes that I've been making when I write grants. I’m going to share some of the mistakes applicants made so that you can improve your applications too: Avoid jargon Some people talked to us like we are technical experts with sentences full of jargon. They treated us like their supervisor at their University. Some of the proposals went way over our heads. Most of them, actually. It seemed like they were trying to impress us. If I have to open Wikipedia to figure out what you are trying to say, it's too much. Don't expand the scope Some proposals offered more than we asked for. We asked applicants to cover three essential points. Some proposals added in fourth and fifth points. That's not what we asked for and there was a reason why we didn't ask for it. Make sure you answer all the questions We specifically asked for a budget from the applicants. One group submitted a proposal and said their organization would have to go through a budget approval process that could take several weeks. Sorry, no, the application needs to be complete. Especially the budget. Ask questions, don’t pitch The groups that performed best in the video interview had a conversation with us; they didn’t try to “sell” us. The other applicants had a PowerPoint presentation full of text and literally read it to us. No bueno—not to mention a snoozefest. The groups who asked questions about what we wanted to accomplish stole our hearts and made it clear they understood the project. They showed us that they’d be fun to work with and not robotic. Some presenters repeated back to us what we already told them in our grant description. We already know about our product; we want to know about you! Avoid sending red flags In one presentation, the Head Applicant’s boss led the discussion. The boss also made the final submission. The optics were off. Either the Head Applicant didn’t care about the project OR wasn’t competent enough to lead the discussion. Why wasn't the Head Applicant presenting and sending us the submission? It just seemed weird. Follow the guidelines The day before the proposal was due, one team emailed me to ask for a one week extension to write their proposal. No, sorry, that’s not going to work. Everyone else worked hard to get their proposal done ahead of the deadline, so please, respect the grantor’s (and your fellow applicants’) time. Be concise Our call for proposals asked for one or two pages but left it open to add more pages. Some groups submitted 14 pages. The winning proposal was just two-and-a-half pages long. Domain expertise goes a long way. Sorry, that’s just how it is. One team’s domain expertise buoyed their application. Even though they lacked detail at times, when they said they could do it on time and on budget we were less skeptical than for groups who were doing this for the first time. It’s worth bringing some expertise to your team, at least in the form of advisors. The decision is not the decision Our decision making process went as follows: first, we scored each application against each criteria in a matrix. Based on the total score, we could rank the proposals from highest-scoring to lowest-scoring. However, the score wasn't the be-all and end-all: it just provided guidance. We then voted on the applications as a committee. Based on my conversations with other grantors, this dual quantitative and vote-by-committee approach is common. Even still, the grant committee’s decision was not final. Ultimately, our CEO, who was responsible for delivering the project to the funders, had the last word. Whatever she chose, informed by our suggestions, would have been the winner in any case. It didn’t come to that, but it could have. Ask for feedback Whenever I apply for a grant and lose, I always ask for feedback. About half the time, the grantor will actually let you know why you lost. In my experience with this sub-grant, not a single group asked for feedback on why they weren’t selected. I was shocked. Personally, I was ready to be completely candid about what they could do to improve. As weird as it may sound, grant writing has become a passion of mine. I was happy to help them improve their applications. But no one asked for feedback, so I never gave any. Until now. Their loss is your gain—because I am now sharing the feedback I wanted to give them with you. They say things happen for a reason. Maybe the reason no one asked is because I was meant to share the feedback with the world. Other resources for writing a good grant application:

USAID’s advice here on how to write a good application rings true to my experience. Many grantors I talk to complain that they can't get enough applicants. So we created a post on how grantors can improve the quality of the applicants they receive.

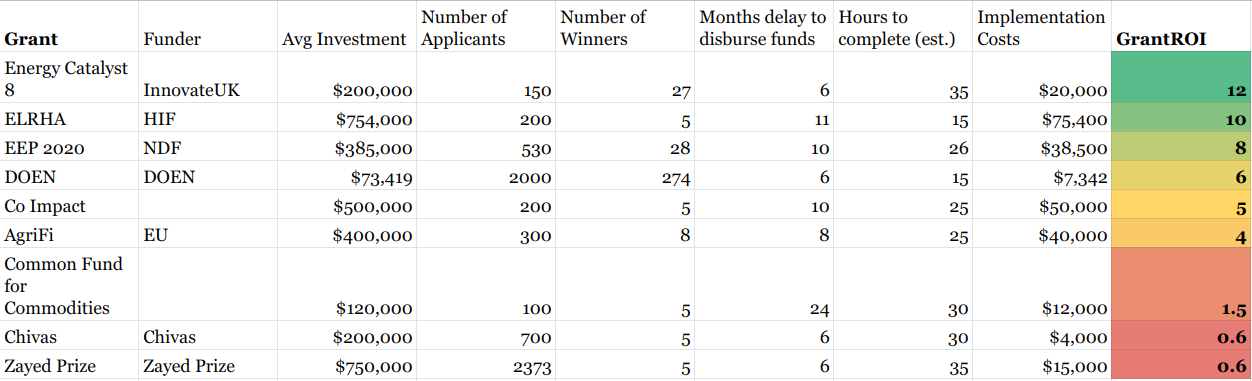

Ever wanted to know whether it was a good idea to apply for a grant? Is it worthwhile? Many people come up with sweeping conclusions that “all grants are a crap shoot” or “grants are good because they are free money.” But the truth is more subtle and I don’t think anyone has published work on this before.

There are many dimensions of whether a grant is worthwhile. What are the chances of winning? Is the prize worth the effort? Once you win will their be so much bureaucracy that the juice isn’t worth the squeeze, as they say?

I remember winning a grant for my biogas company several years ago. We were so excited. And then it took 18 to get the money. We were almost out of business by then. And we had only survived because I stopped taking a salary for a few months.

Whether to apply for a grant seems like more art than science. However, I think that we can quantify this. Any time you take on a new project one way to think about it is ROI. If you spend $1,000 on ads, how many sales are you going to get. We can do the same for grants. I’m calling the metric of how worthwhile it is to apply for a grant the GrantROI. Nuts and Bolts I’ll explain the formula here. Feel free to skip to Results below if it is too detailed.

Where

and

Let me dig into a few of these variables. TimeDelay. Because time is money, you’d rather have the money now than 18 months from now when you might be out of business. This is the delay between the application deadline and the day the winner gets cash in the bank. There is a way to account for this using a Net Present Value calculation which you can read about on wikipedia. To figure out how much to discount future cash flows you use an interest rate. Typically the prevailing bank interest rate (let’s say 16% in Kenya) plus an additional factor for the added risk you experience as a startup, perhaps an additional 10-20%. The NonMonetaryGrantValue is usually zero, but in the case of a startup accelerator most of the value might be in the network you make rather than the cash they award you. YourTime and GrantWriterTime is how long it will take to complete the application. I broke down each application into parts and figured out how many hours I would bill a client to complete the application and set YourTime to 10 hours for each application for general oversight and editing my proposal. Clearly this formula rewards grantors for having shorter applications. ImplementationCosts is an especially important factor. If a grantor awards you $100,000 but expects you to conduct M&E activities and reporting that will cost you $90,000 the grant is obviously not worth it. That's just too many hoops to jump through.

Chances of winning can be derived from previous calls for proposals from the same Grantor or from their annual report where they say “we received x applicants and gave y awards.”

There are other features that I thought of including in the formula which might make it into the next version such as whether the grantor provides feedback on rejected applications (which is a non-Monetary value) and whether the grantor hosts multiple rounds which enables applicants to improve their application from one year to the next. Whether grantors respond in a timely manner was another factor I considered, but that can be part of the ImplementationCosts variable as timeliness should decrease ImplementationCosts. The general idea would be to reward all good behavior of grantors so that more are better to work with.

So what are the best grants to apply for and what are the worst?

The results are pretty clear. Some grants are clearly not worth applying to. For any grant with a GrantROI of less than 1 it means that the grantor is adding less dollars to the sector than it is sucking out in terms of applicants' time.

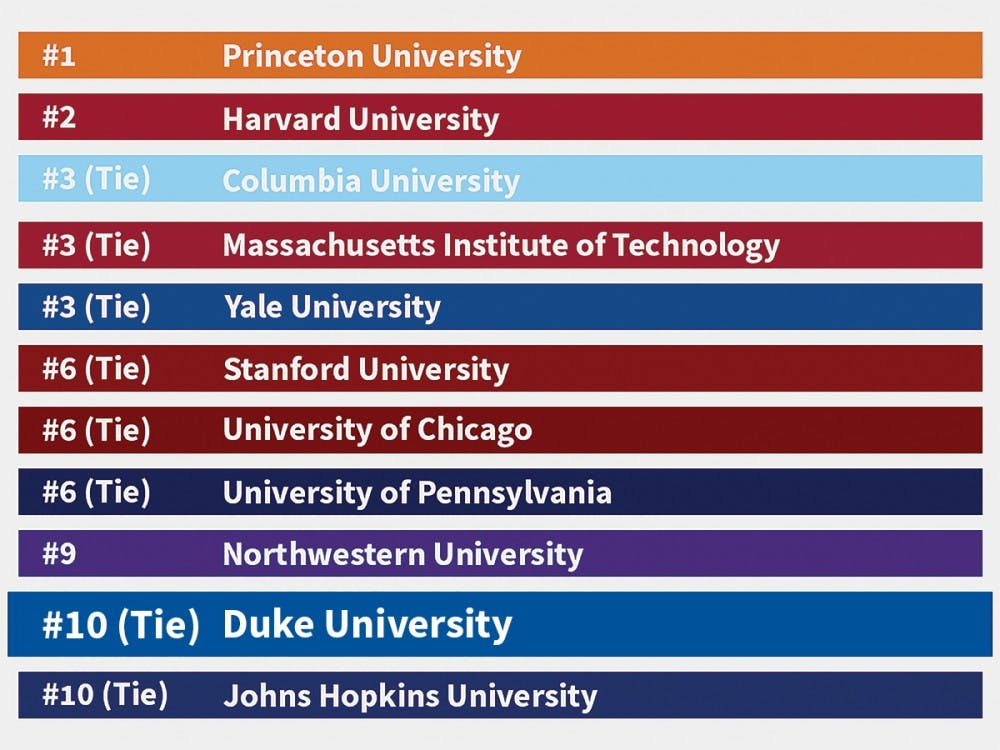

This GrantROI is only correct for the average applicant. Perhaps your application is an especially good fit or you have a personal connection that increases your chances. That would increase your GrantROI. Furthermore, you are not a lottery ticket. Just because you submit an application doesn’t give you a fixed probability of winning; a lot depends on the quality of the application. So GrantROI is not a silverbullet solution to determine whether you should apply. But! I hope this is a useful tool as a first step. Just as US News and World Report publishes an annual college ranking, I hope we can make a grantor ranking. This could create more accountability for grantors to have entrepreneur-friendly applications.

If you have data points for other grantors you’d like me to add let me know by email or by commenting on this post. If you know of a good place to publicly host a ranking wiki let me know as well so that other people can edit this list with more updated info.

To use this tool (and other tools I developed) click here. |

AuthorKyle founded Grant&Co after running a biogas company in Kenya for 5 years. We raised a lot of grant capital there. And now we help other entrepreneurs raise capital. Archives

November 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed